In my last post, I talked about a storage engine I'm building called store. While it's gone in a different direction, it initially started out as a library-style storage engine using a bw-tree as the underlying indexing structure. I like a lot of the ideas from the bw-tree (and LLAMA in general), but to me it's main flaw is that it needs a lot of extra ancillary mechanisms to mitigate edge cases and issues that arise from wanting lock-free access. In particular, the garbage collection and system transactions feel like band aids to me. On top of that, having arbitrarily sized pages represented by separately allocated nodes in a linked list makes the already cumbersome garbage collection (and memory management in general) much more complicated that it needs to be in my eyes.

One piece of the LLAMA paper did stick out to me as having a very similar workload requirement to pages, but with a substantially more simple implementation: the flush buffers. I won't go into a ton of detail here, but the specific idea that interested me was that threads would "seal" these buffers when they became full, and this would simultaneously block other threads from manipulating the data, and automatically choose a thread that would be responsible for handling this sealed buffer. Additionally, the data is laid out in a much more straightforward way that meshes more with how I think about data manipulation (what can I say, I'm a sucker for large contiguous fixed-size buffers of raw bytes 🤷). So, I decided to explore what implementing pages with these ideas would look like, and I came up with something that seems pretty interesting to me, and has a fairly unique mechanism for shifting between lock-free and exclusive lock-esque access. I'm just gonna call them "seal buffers" to have a word to use for talking about them (I really hate naming things).

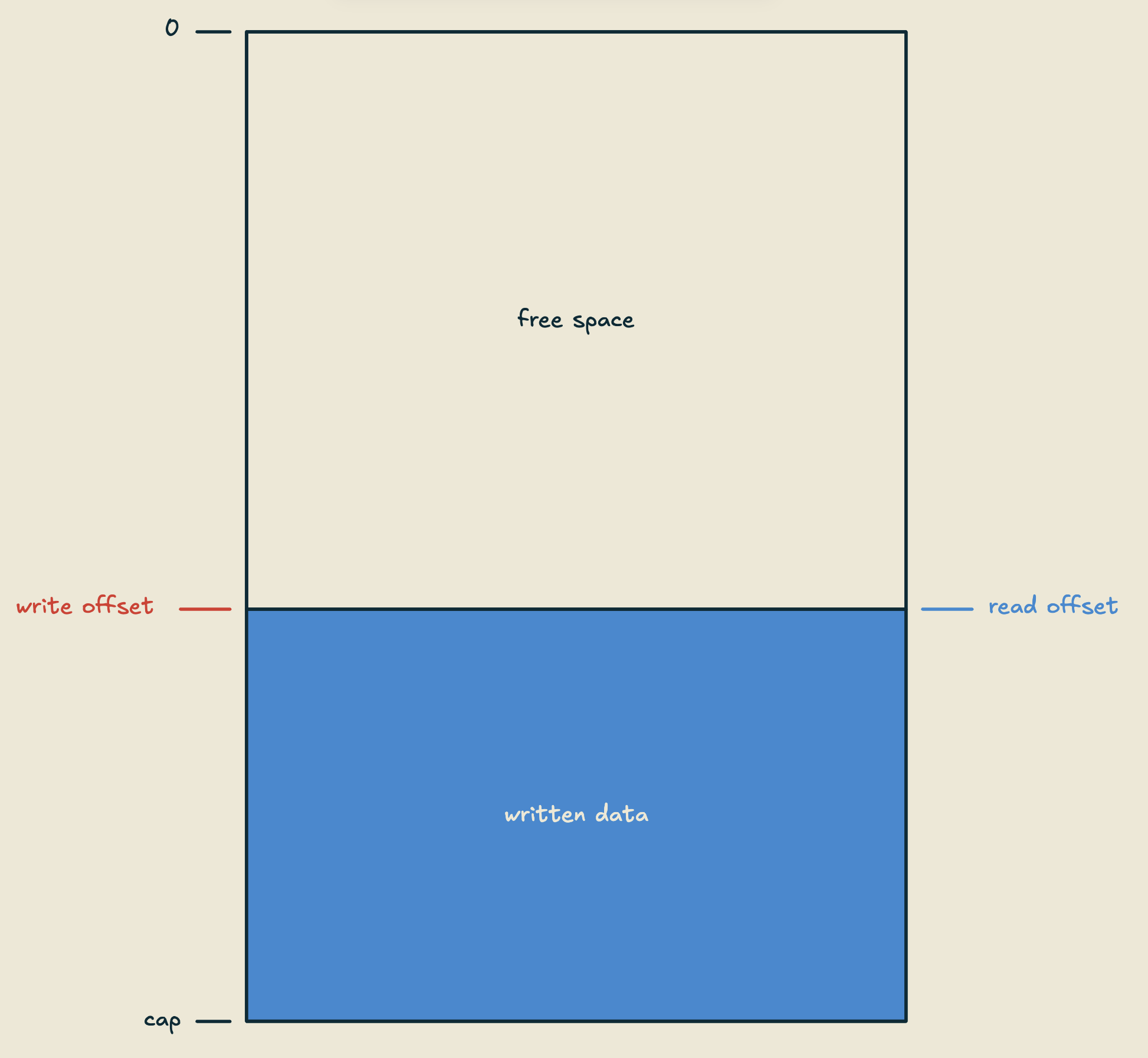

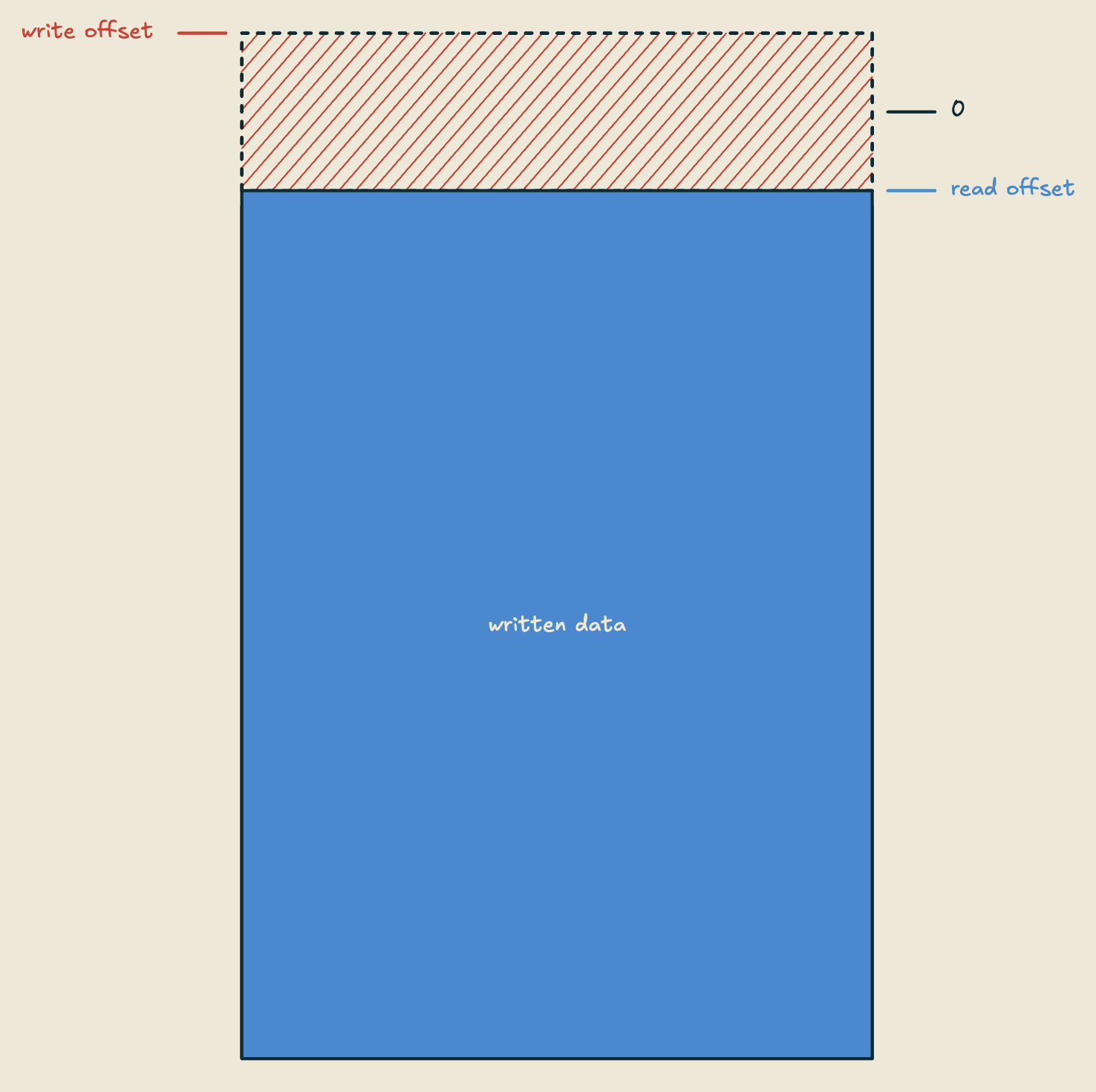

So let's take a look at how seal buffers work. We have a fixed length buffer of bytes, that I like to think of conceptually as having a "top" and "bottom", where the top is at the 0th index, and the bottom is at the capacity-th index. There are two atomic integers: a read offset, and a write offset. The read offset is unsigned, and the write offset is signed (for reasons we'll see in a second). It looks something like this:

struct SealBuf {

ptr: ptr::NonNull<u8>,

cap: usize,

read_off: atomic::AtomicUsize,

write_off: atomic::AtomicIsize,

}

Reading is pretty simple, we just atomically load the read offset, and return a slice of data "below" the offset, like so:

impl SealBuf {

// ...

fn read(&self) -> &[u8] {

let read_off = self.read_off.load(atomic::Ordering::Acquire);

unsafe {

slice::from_raw_parts(

self.ptr.add(read_off).as_ptr(),

self.cap - read_off,

)

}

}

// ...

}

This gives us a contiguous section of bytes in reverse chronological order, no pointer chasing required, and under normal operation, readers are never blocked and never have to wait on other threads to make progress (i.e. reading is wait-free).

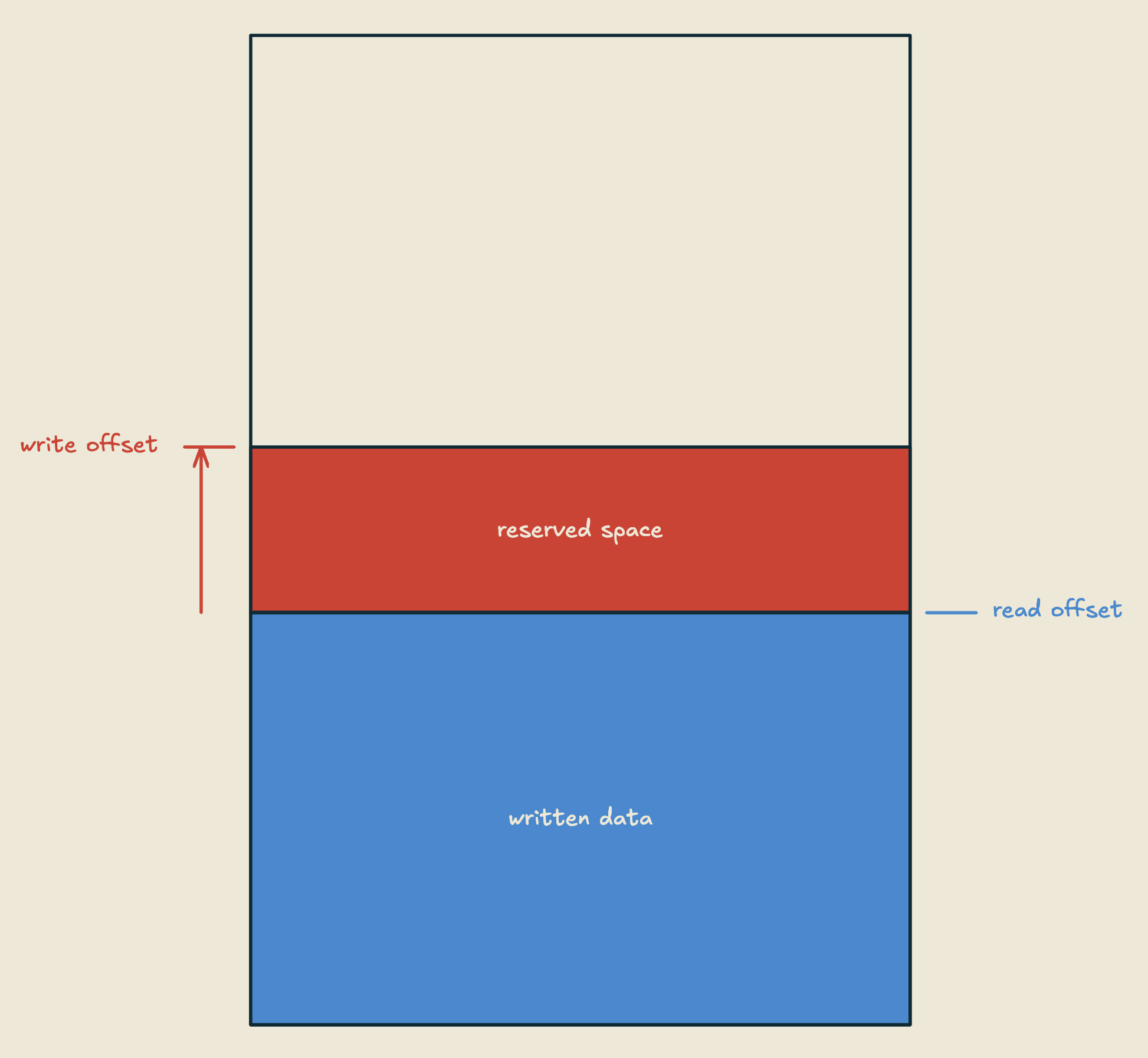

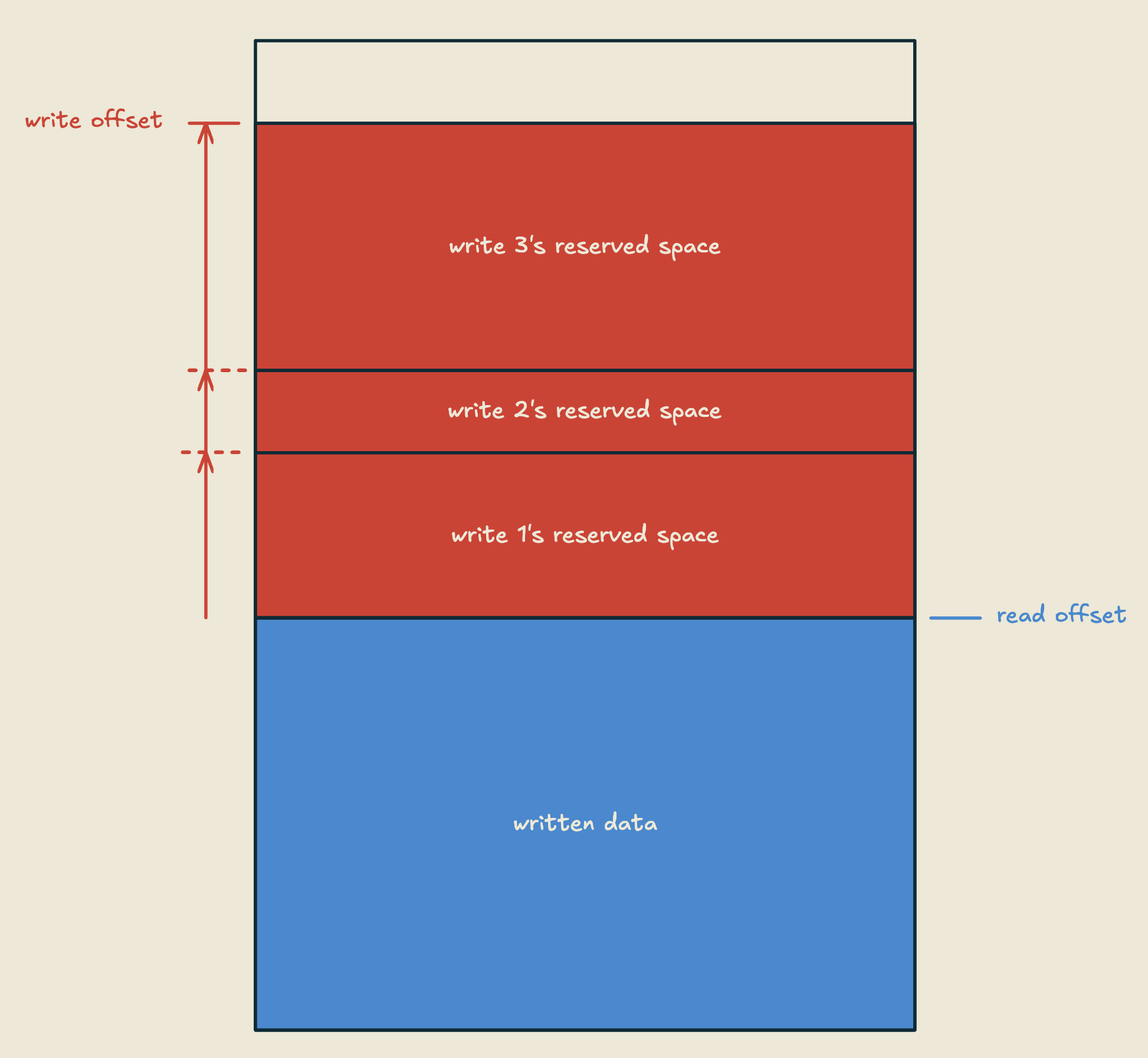

Writes are slightly more complicated. To perform a write, a thread will first reserve space for it's write by performing a fetch_sub on the write offset, by the size of the data it's trying to write.

We can have multiple writers concurrently reserving space without blocking each other (for the reservation of space specifically, also fetch_x ops a lot of the time are implemented as (very short lived) CAS loops, so depending on your definition of what "blocking" means, this might not be completely true), and they have no impact on readers.

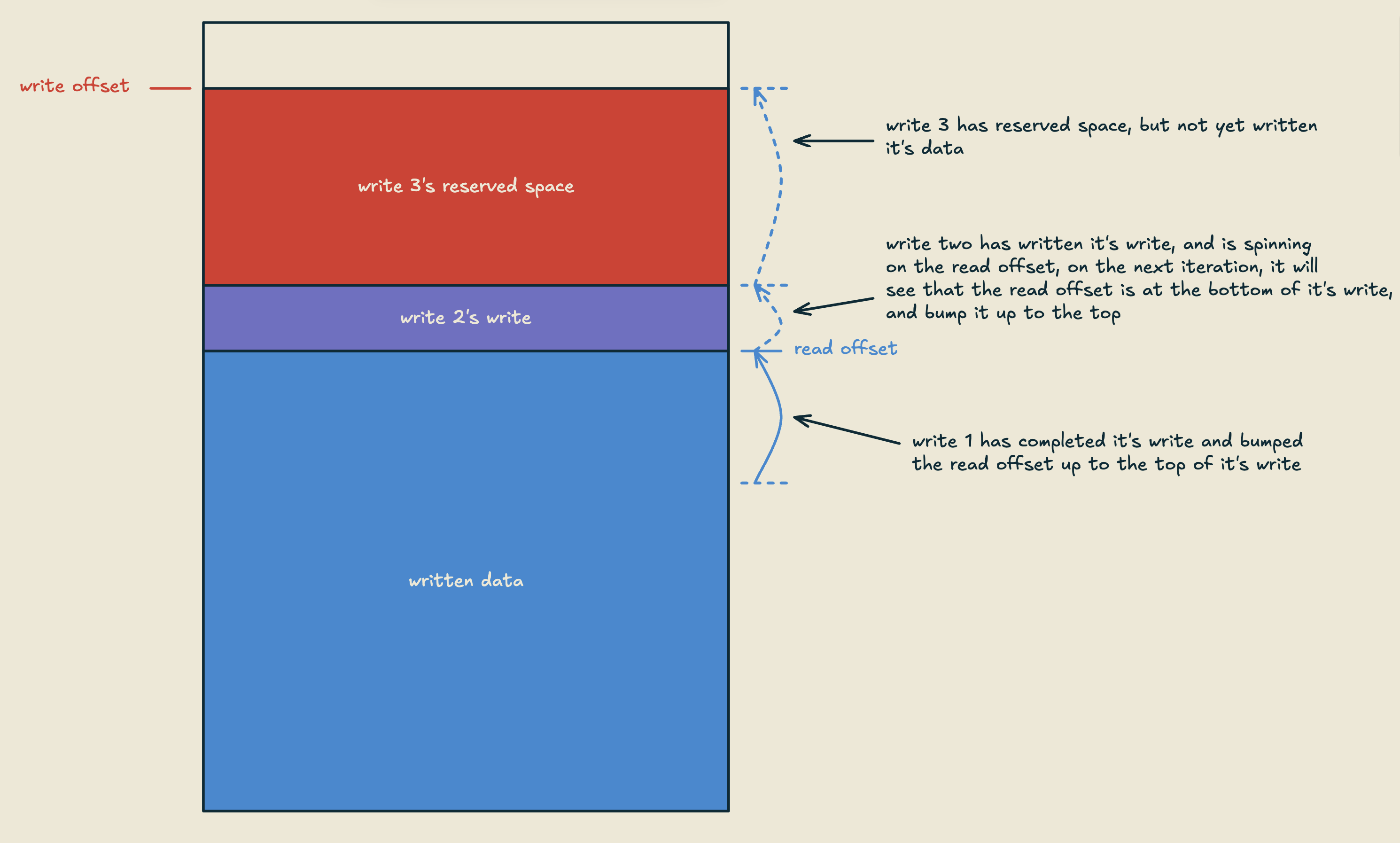

For committing a write, we need to preserve the validity of any reads being done, which means writes need to commit in the order they were reserved. Once a writer finishes copying it's bytes into the reserved space, it will spin (very briefly) waiting for the read offset to equal the bottom of it's write, at which time it will store the top of it's write into the read offset. This ensures that any given write will only commit after any write below it is finished, and by revealing it's data to readers, it will also trigger any writes above it to commit.

It's worth noting that the write path here needs to be very short, for a couple of reasons. One is that, on commit, we essentially have a spin lock. For very short time periods, this approach can perform extremely well, but if we end up in a situation where we're waiting on a write below us for a long time, we've essentially blocked n writers from committing that may be above us, this will absolutely kill our performance. The second reason is that this approach requires that individual threads can't fail in the write path. If our whole system crashes, that's fine, but if some threads fail and others are still going, that's a big problem. In Rust, this basically amounts to making sure that we don't panic in the write path.

All of this means that we really don't want the same interface as our reads for writes, where we maybe hand out a &mut [u8] and let writers tell us from the outside when they're done. This would make our write path take an indeterminate (from the data structure's perspective) amount of time, and we have no control over whether the caller will do anything that may cause a panic. So, instead, we want to have the data being written accepted as an argument, and handle the entire write path ourselves inside a single function.

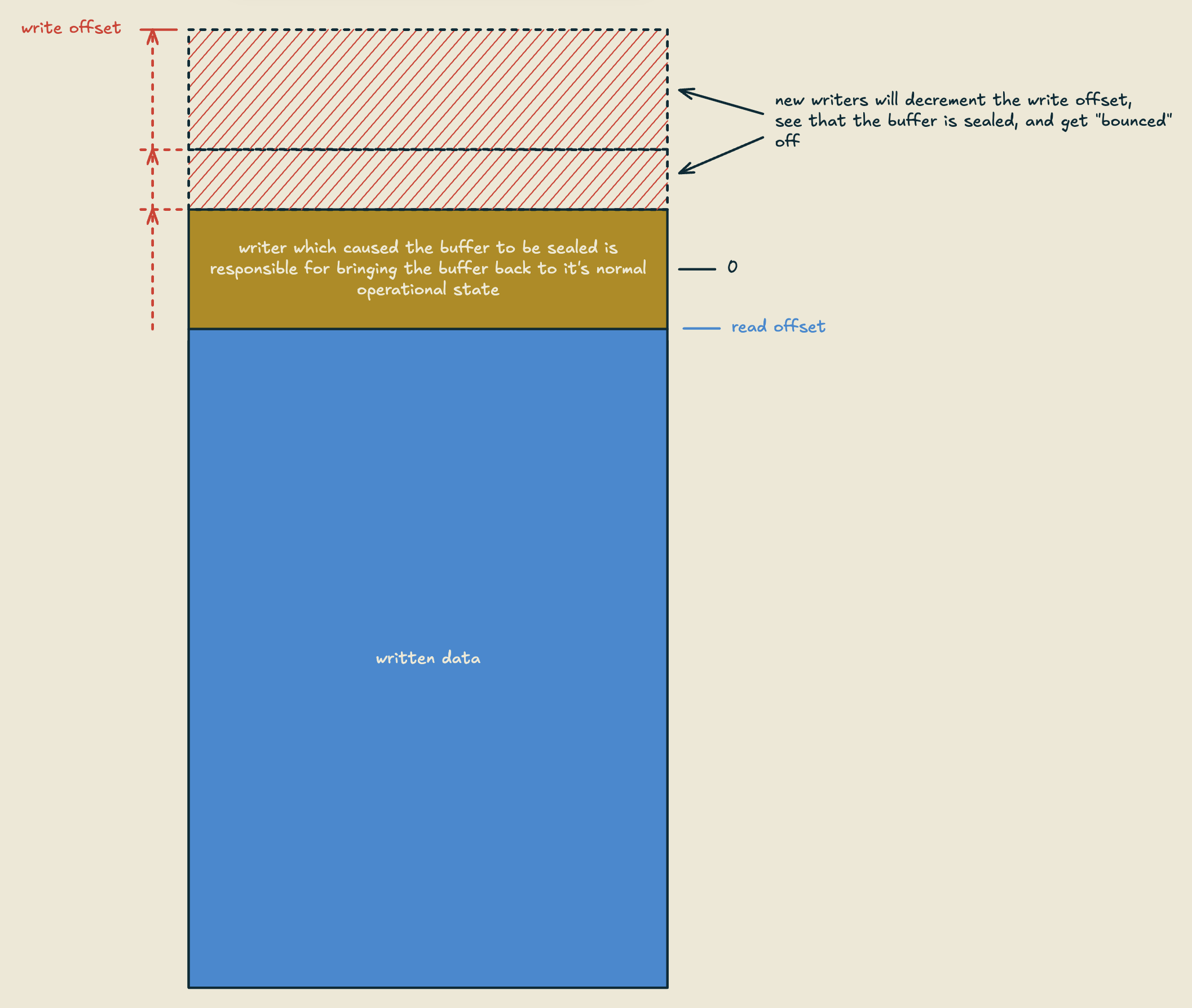

Now, before I show you the code for the write path, we need to talk about what happens when the buffer becomes full. This is where things get interesting, and where the upgrade path for this structure offering exclusive access starts. When a writer reserves space beyond the capacity of the buffer (write_off becomes negative), the buffer is considered "sealed" to any new writers.

Any new writers coming in will see that the write offset is negative, and will simply fail. The writer which caused the write_offset to go negative is then responsible for bringing the buffer back to it's normal operational state. Going forward, we'll call this writer the sealer. Once the sealer sees that the read offset equals the bottom of the space it tried to reserve, we know that there are no more current writers accessing the data, and that any new writers will be "bounced" from accessing the data.

At this point, the data is essentially read-only, and notably, throughout this whole process so far, readers are still completely unaffected. In a bw-tree setting, what might happen next would maybe look something like:

- sealer compacts the data into a new base page in a new buffer

- sealer loads (don't need CAS because there's only one writer at this point) the newly minted base page into the mapping table

- sealer hands off the sealed buffer to some kind of pool that handles GC

This isn't drastically different to typical bw-tree operation, but we've massively simplified our memory management by using fixed-sized buffers, and our reads should be significantly faster. Without any additional mechanisms, our write path might look something like this:

impl SealBuf {

// ...

fn write(&self, buf: &[u8]) -> WriteRes {

let old_write_off = self

.write_off

.fetch_sub(buf.len() as isize, atomic::Ordering::AcqRel);

let new_write_off = old_write_off - buf.len() as isize;

match new_write_off {

n if n < 0 && old_write_off >= 0 => {

// caused buffer to be sealed

// wait for other writers to finish

while self.read_off.load(

atomic::Ordering::Acquire,

) != old_write_off as usize {}

WriteRes::Sealer(Seal {

// ...

})

}

n if n < 0 => {

// buffer is sealed but we didn't cause it

WriteRes::Sealed

}

_ => {

// we have reserved room for the write

unsafe {

ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(

buf.as_ptr(),

self.ptr.add(new_write_off as usize).as_mut(),

buf.len(),

)

}

while self.read_off.load(

atomic::Ordering::Acquire,

) != old_write_off as usize {}

self.read_off

.store(new_write_off as usize, atomic::Ordering::Release);

WriteRes::Ok

}

}

}

// ...

}

enum WriteRes {

Ok,

Sealed,

Sealer(Seal),

}

struct Seal {

// ... some data for accessing the buffer in this read-only way

}

Now, if we want, we can take this "sealing" concept a step further, and potentially completely eliminate the need for any kind of GC, and maybe even get rid of the weird "system transactions" that the bw-tree needs to pull off structure modifications. To do this, we can just use the same concept of basically moving the read offset to some invalid number (for now, this will just be cap + 1), then, when new readers try to access the data, if they see this invalid offset, they know that the buffer is sealed to readers, and similar to writers, they simply fail. Then, if we have some mechanism for knowing when any current readers are done, if our buffer is sealed to both readers and writers, our sealer has exclusive access to the buffer, and can access and modify it at will, as if it had a mutex on the data.

For the "knowing when readers are done" mechanism, there are a lot of options here (hazard pointers, epochs, etc), and they all have their pros and cons, but for now I'll just show the simplest option: reference counting. This is similar to how std::sync::Arc functions, but instead of using it to know when data is safe to drop, we're using it to know when data is safe to modify. To be clear, adding this mechanism in any capacity will definitely slow down our reads to a certain extent, but we get a lot of power for that cost here, so in a lot of cases, it's probably worth it.

So, looking at the code, we can start by modifying our read function in two ways. First we need to check if the buffer is sealed to readers, and if so fail accordingly. Second, if the buffer is not sealed, we'll increment a reference count, and return a guard which derefs to a &[u8], and when dropped, decrements the ref count, like so:

struct SealBuf {

ptr: ptr::NonNull<u8>,

cap: usize,

write_off: atomic::AtomicIsize,

read_off: atomic::AtomicUsize,

read_count: atomic::AtomicUsize,

}

impl SealBuf {

// ...

fn read(&self) -> Result<ReadGuard, ()> {

let read_off = self.read_off.load(atomic::Ordering::Acquire);

if read_off <= self.cap {

self.read_count.fetch_add(1, atomic::Ordering::Release);

Ok(ReadGuard {

slice: unsafe {

slice::from_raw_parts(

self.ptr.add(read_off).as_ptr(),

self.cap - read_off,

)

},

read_count: &self.read_count,

})

} else {

Err(())

}

}

// ...

}

struct ReadGuard<'g> {

slice: &'g [u8],

read_count: &'g atomic::AtomicUsize,

}

impl Deref for ReadGuard<'_> {

type Target = [u8];

fn deref(&self) -> &Self::Target {

self.slice

}

}

impl Drop for ReadGuard<'_> {

fn drop(&mut self) {

self.read_count.fetch_sub(1, atomic::Ordering::Release);

}

}

Now that we have that piece, we can modify our write path to seal the buffer to readers as well when it find that it's sealed it to writers. The flow for a bw-tree system using seal buffers as pages would be as follows:

- when a thread becomes a sealer, first, wait for any writers to finish (the spin on the read offset)

- then, store cap + 1 in the read offset, sealing the buffer to any new readers

- then, since there are no more writers, we can read the buffer, and perform a compaction in some other scratch space that is uniquely suited to that workload. doing this compaction work will also allow time for current readers to finish doing their work.

- then, wait for any straggling readers to finish up, at which time we have fully exclusive access to the buffer, and we can serialize the newly compacted base page back into the original buffer, and reset the offsets accordingly

Now, this isn't that different from what the original bw-tree paper does, but the key distinction is that this mechanism allows us to stop any new readers before we do compaction, not after. This means, in a lot of cases, current readers will be gone by the time we finish compaction, and we can just reuse the space directly without any waiting. Our memory management picture has become drastically more simple.

So, in the code, our write path might look something like this now:

impl SealBuf {

fn write(&self, buf: &[u8]) -> WriteRes {

let old_write_off = self

.write_off

.fetch_sub(buf.len() as isize, atomic::Ordering::AcqRel);

let new_write_off = old_write_off - buf.len() as isize;

match new_write_off {

n if n < 0 && old_write_off >= 0 => {

// caused buffer to be sealed

// wait for other writers to finish

while self.read_off.load(

atomic::Ordering::Acquire

) != old_write_off as usize {}

// bounce new readers

self.read_off.store(self.cap + 1, atomic::Ordering::Release);

WriteRes::Sealer(Seal {

buf: &self,

true_read_off: old_write_off as usize,

})

}

n if n < 0 => {

// buffer is sealed but we didn't cause it

WriteRes::Sealed

}

_ => {

// we have reserved room for the write

unsafe {

ptr::copy_nonoverlapping(

buf.as_ptr(),

self.ptr.add(new_write_off as usize).as_mut(),

buf.len(),

)

}

while self.read_off.load(

atomic::Ordering::Acquire,

) != old_write_off as usize {}

self.read_off

.store(new_write_off as usize, atomic::Ordering::Release);

WriteRes::Ok

}

}

}

}

enum WriteRes<'r> {

Ok,

Sealed,

Sealer(Seal<'r>),

}

struct Seal<'s> {

buf: &'s SealBuf,

// we need this so that we can easily read just the stuff that has actually

// been written (there will be a tiny sliver of empty space at the top)

true_read_off: usize,

}

impl<'s> Seal<'s> {

pub fn wait_for_readers(self) -> ExclusiveSeal<'s> {

while self.buf.read_count.load(atomic::Ordering::Acquire) != 0 {}

ExclusiveSeal {

buf: self.buf,

true_read_off: self.true_read_off,

}

}

}

impl Deref for Seal<'_> {

type Target = [u8];

fn deref(&self) -> &Self::Target {

unsafe {

slice::from_raw_parts(

self.buf.ptr.add(self.true_read_off).as_ptr(),

self.buf.cap - self.true_read_off,

)

}

}

}

struct ExclusiveSeal<'s> {

buf: &'s SealBuf,

true_read_off: usize,

}

impl ExclusiveSeal<'_> {

pub fn reset(self, top: usize) {

self.buf.read_off.store(top, atomic::Ordering::Release);

self.buf

.write_off

.store(top as isize, atomic::Ordering::Release);

}

}

impl Deref for ExclusiveSeal<'_> {

type Target = [u8];

fn deref(&self) -> &Self::Target {

unsafe {

slice::from_raw_parts(

self.buf.ptr.add(self.true_read_off).as_ptr(),

self.buf.cap - self.true_read_off,

)

}

}

}

impl DerefMut for ExclusiveSeal<'_> {

fn deref_mut(&mut self) -> &mut Self::Target {

unsafe { slice::from_raw_parts_mut(self.buf.ptr.as_ptr(), self.buf.cap) }

}

}

And the code for the bw-tree implementation would look something like:

// ...

match seal_buf.write(&delta) {

WriteRes::Ok => {}

WriteRes::Sealed => {

// some kind of cancel or backoff or wait, depends on the implementation

}

WriteRes::Sealer(seal) => {

compact_page(&seal, &mut scratch);

let exclusive = seal.wait_for_readers(); // should be a pretty short spin

let new_top = serialize_page(&scratch, &mut exclusive);

exclusive.reset(new_top);

// you'd also still need to do something with that delta,

// maybe `scratch` has methods for applying in place updates,

// maybe you'd still want to handle splits and merges, etc,

// again depends on the implementation

}

}

// ...

Additionally, we can use this sealing mechanism in a much more general purpose way than we've laid out here. For example, when doing structure modifications, we have the option to eliminate the system transaction mechanism of the bw-tree/LLAMA by essentially using our seal mechanism as a lock (and better yet, a lock that we can trigger without necessarily waiting, we can start the process of having exclusive access, and do other work in the meantime). We also don't necessarily need a full seal every time, and we have the option to use the structure in this way, we can seal to writers, and keep readers going.

This is far from a bulletproof implementation of this idea, there are lots of bells and whistles to add (async for waits if we wanted to, buffers that work by appending rather than prepending, etc). It's also worth noting that lock free data structures, especially (relatively) novel ones, are easy to get wrong in very subtle ways. There are probably subtle bugs and weird edge cases here, and it's not an obvious performance win by any means (and depending on how it's used, maybe not a performance win at all). What it is however is a massive simplicity win for systems that need this kind of data structure. By being able to have lock free access (with minimal waiting) to our data under normal operation, but upgrade to exclusive access when we need it, we can eliminate a lot of the ancillary mechanisms that systems using lock free data structures often need.

I won't actually be using this in store, since I've gone a different route with the concurrency approach, but it seemed like an interesting and unique enough idea to share. Hopefully you've enjoyed hearing (reading?) me ramble about it. Til' next time!